Jennifer Préfontaine, Michele Tenzon, Ewan Harrison, Iain Jackson, Claire Tunstall, and Rixt Woudstra discuss changing terms in archival descriptions

Republished from CCA website.

This is the first article in a series that considers reflections on the value of interpretation in combination with the technical practice of cataloguing, authored by CCA staff and invited scholars and introduced by Martien de Vletter. Here, we examine changing terminology. CCA cataloguer Jennifer Préfontaine considers context and the use of the term “peon” in cataloguing the Pierre Jeanneret fonds, and Michele Tenzon, Ewan Harrison, Iain Jackson, Claire Tunstall, and Rixt Woudstra sift through reworkings that were made in the development of the United Africa Company archives.

The Importance of Context

Jennifer Préfontaine weighs meaning and intent when cataloguing archival materials

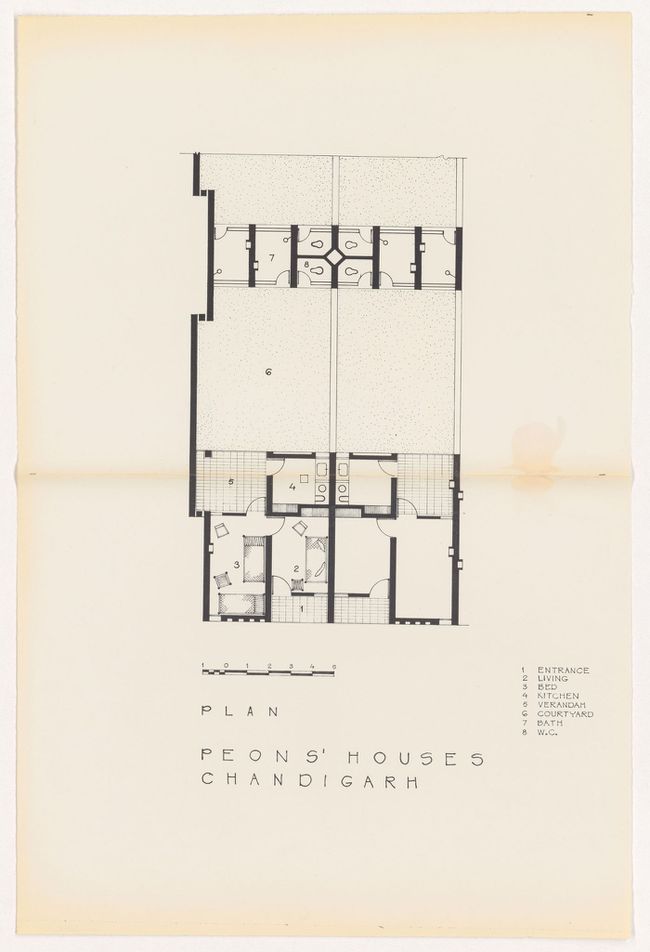

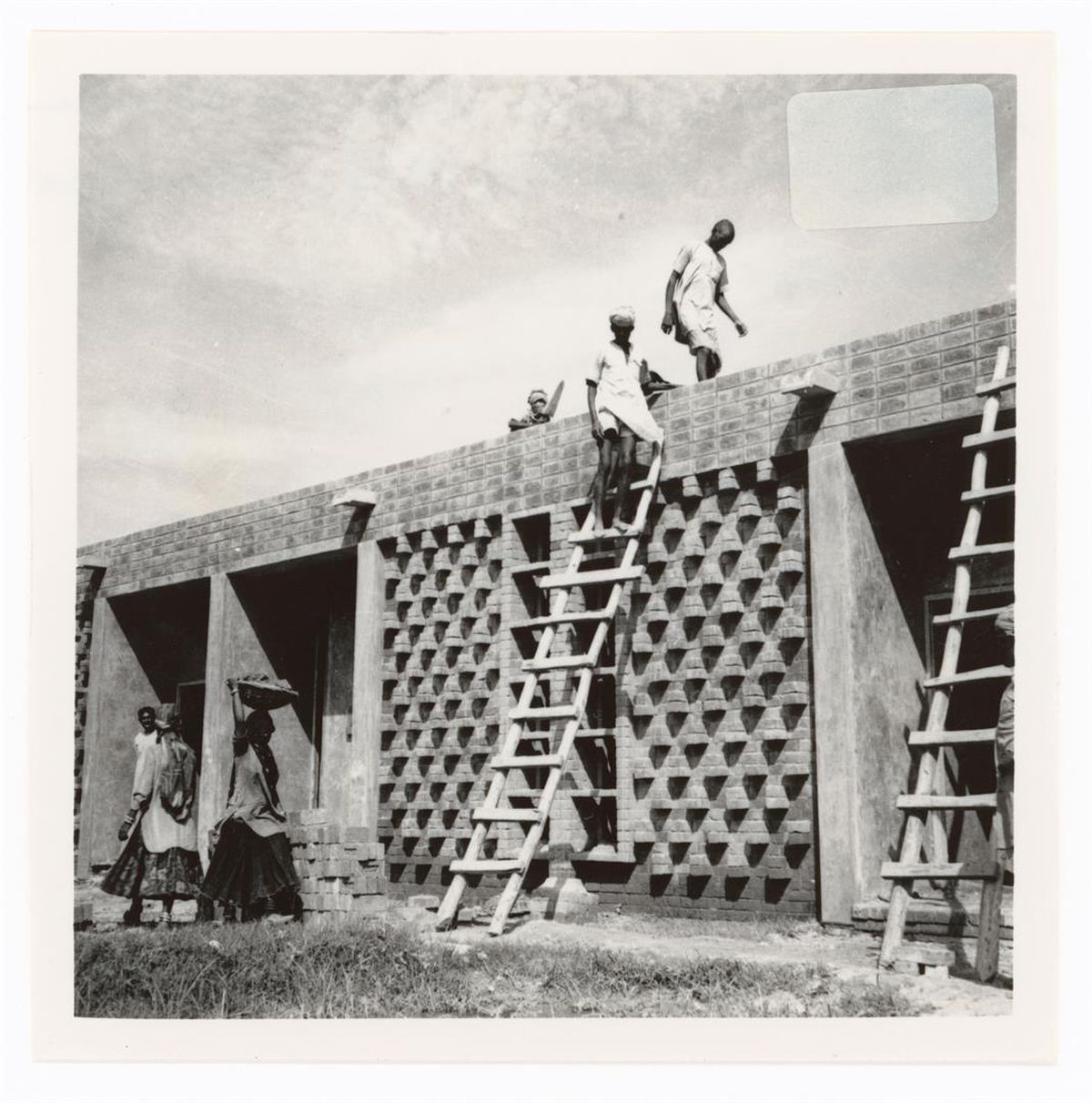

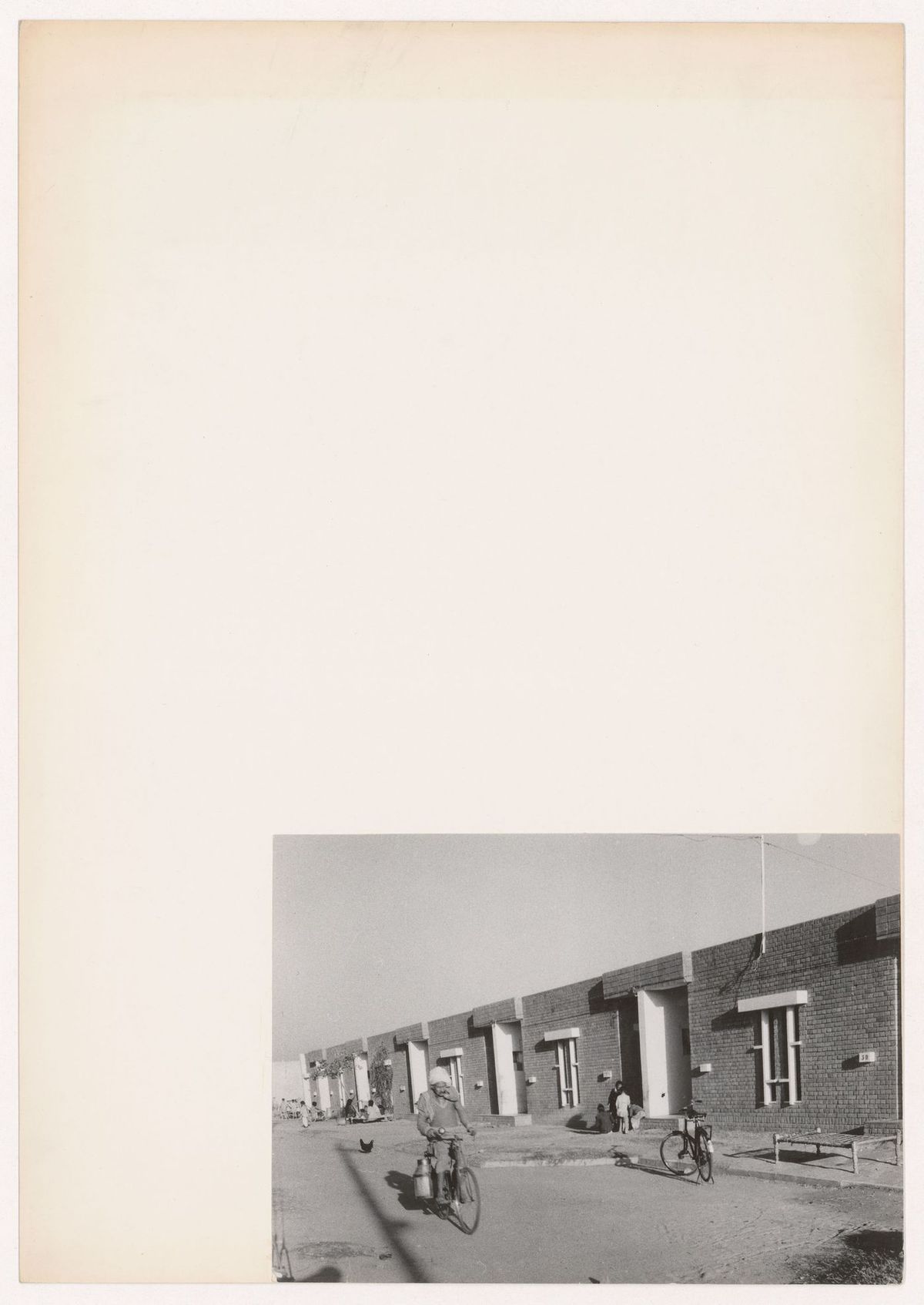

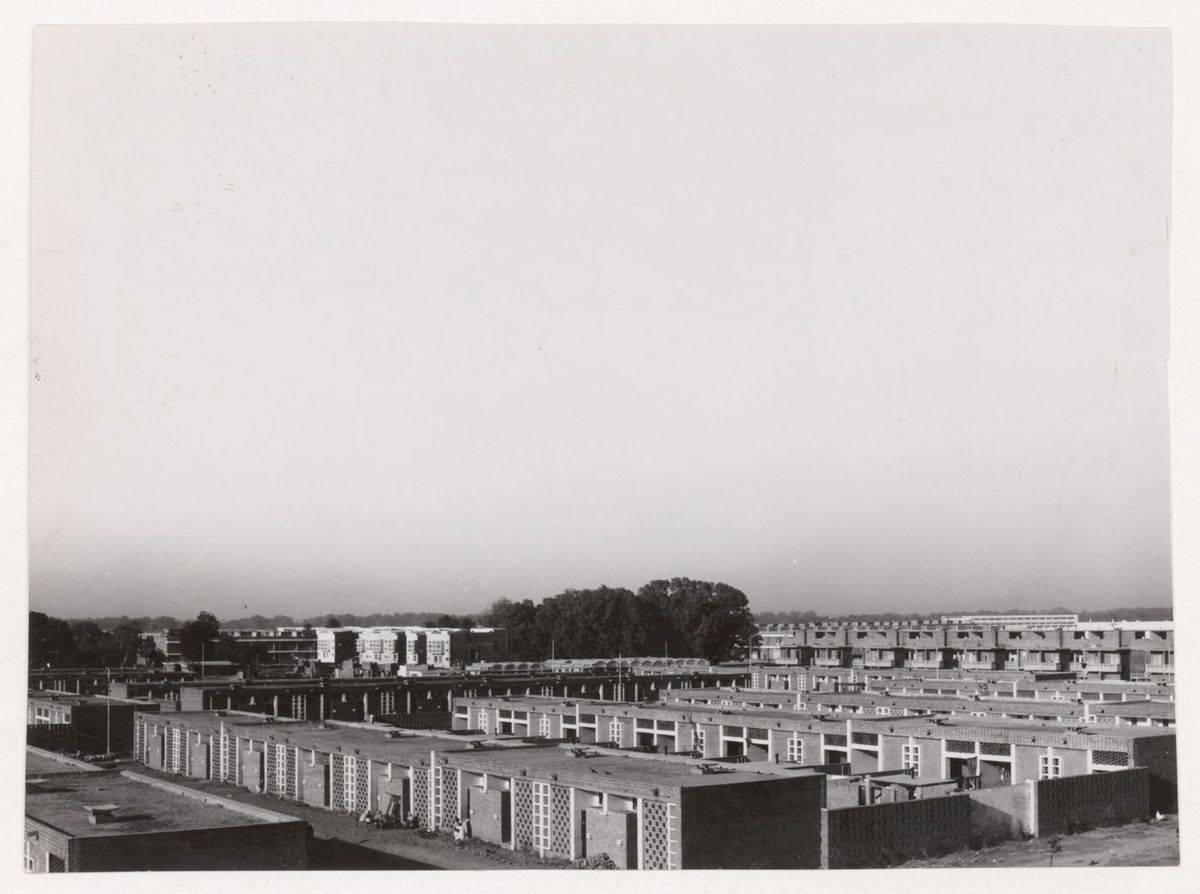

During Sangeeta Bagga’s Find and Tell residency in June 2019, we—the cataloguers at the CCA—came across material using a word with which we were uncertain. A plan drawing, held in the Pierre Jeanneret fonds that Bagga was studying, labels “Peons’ Houses” as the title of a project in Chandigarh, from 1952.1 From definitions found in print and online dictionaries, we felt that “peon” could be understood as harmful in some contexts but neutral in others. A word can have different meanings, different geographies, and even different histories, in particular colonial histories. In cataloguing work, the choice of vocabulary has important implications in how researchers access and understand information. We needed to consider, is there a problem with the use of the word “peon” when identifying people?

We learned that the word “peon” has different meanings and origins depending on where and when the term is used. Among other definitions, it means a labourer or a non-specialized worker.2 In Latin America, especially in Mexico, a “peon” has additionally come to denote a labourer that has an obligation to work for their employer until their debt was paid off.3 This type of “labor practice”4 has served as the basis of what would become known as “peonage” in the period after the abolition of enslavement in the United States, where many African American freedmen and freedwomen with limited options were forced and bound into this system that maintained an involuntary servitude.5 6 It seems within this American context that the use of this word in cataloguing should be reassessed. However, comparatively, in South Asian countries, particularly in India and Sri Lanka, the word “peon,” brought by the Portuguese, historically meant a foot soldier or a police officer.7 These days, it refers, in an Indian context, to a messenger or attendant, especially in an office,8 designating the entry-level position in governmental and non-governmental organizations.9 10

Considering that the materials from the Pierre Jeanneret fonds that include the word “peon” in their descriptions are related to Chandigarh, would it be acceptable to use the term despite the negative connotation it bears in another context, especially the American one? Shall we use a different term, or keep this “contentious” word with the possible addition of a contextual note?

As the CCA is an international institution located in North America, we wonder if it is preferable to remove a word that is potentially harmful from our descriptions, even if it remains in use and seemingly appropriate in other cultural contexts. What about the research behaviour of our users? Experts on Chandigarh, particularly on Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s works, might be expecting the word “peon” and search for it in our catalogue. In order to understand the use of this term within the framework of the study of Indian architecture and society, we decided to reach out to experts of this field of research.

For Dr. Sangeeta Bagga,11 Principal at Chandigarh College of Architecture, Vikram Bhatt,12 author of Blueprint for a hack, Resorts of the Raj, and After the masters, and Dr. Vikramāditya Prakāsh,13 author of Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier and One Continuous Line, and editor of Rethinking Global Modernism, the word “peon” is an appropriate term used to designate an entry-level position at government levels in India. However, they point out that private corporations do not generally use the term anymore. Bhatt mentions that an equivalent word is “chaprasi,” and there might be other equivalent terms in other regions of India. Bagga argues that, although “office boy” is the term currently used in the private sector, “peon” still describes a position that allows people to work in dignity in a non-technical job, and people in India do not necessarily associate the word with a colonial background. It was institutionalized under the British period, but it still is in use today, without any negative connotations. Both Bhatt and Prakāsh acknowledge that while the term is still in use, it is not a word used in everyday conversation. To them, it could carry derogatory implications, depending on how it is used.

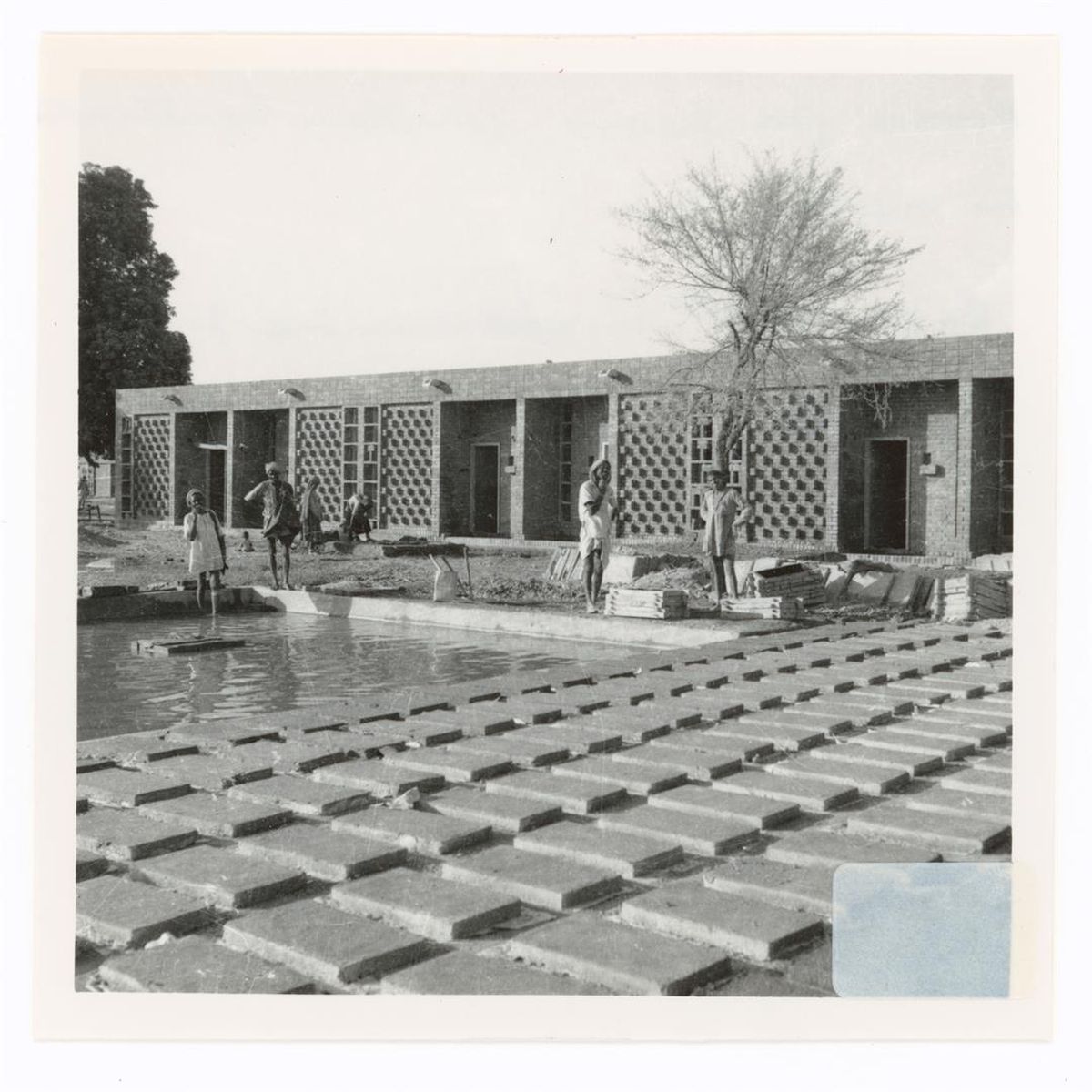

Bagga and Bhatt also mention that Chandigarh is a city that was laid down to a precise hierarchy initially with thirteen types of government housing in which the “peons” were at the lowest end.14 Bagga adds that with Jane Drew and Pierre Jeanneret’s work, it was the first time that the “peons” had planned housing accommodations.15 She underlines that the architectural drawings and other materials attest to this nomenclature; this type of housing was specifically called “peons’ houses,” as is depicted in the plan’s title. If the word is absent from the description, how would a researcher find it?

We might not be able to dissociate the use of the word from the context in which it appears. Prakāsh recommends keeping the term with respect to the Pierre Jeanneret fonds, noting that there is not a “right” interpretation of a word, certainly not based on an “original” meaning. For Bhatt, for as long as there have been contacts between the Western and Eastern worlds, languages have mutually influenced each other. With this in mind, Bhatt said that he would not be hesitant to use this word, but cataloguers should certainly recognize the different contexts in which it is used.

From these discussions, it seems apparent that the word “peon” carries different weights and meanings based on its context. All three experts recommend that we continue to use “peon” in our descriptions as part of the title field, and that we should add, if relevant, a contextual note explaining the word. As we recognize the importance of examining the changing meaning of words over time and context, especially when they are used in relation to how you refer to people directly, processes like this one, will help us set guidelines for more mindful descriptive work.

We would like to thank Sangeeta Bagga, Vikram Bhatt, and Vikramāditya Prakāsh for sharing their thoughts on this topic.

Reworking, Recaptioning, Moving Beyond

Michele Tenzon, Ewan Harrison, Iain Jackson, Claire Tunstall and Rixt Woudstra examine the Archives of the United Africa Company.

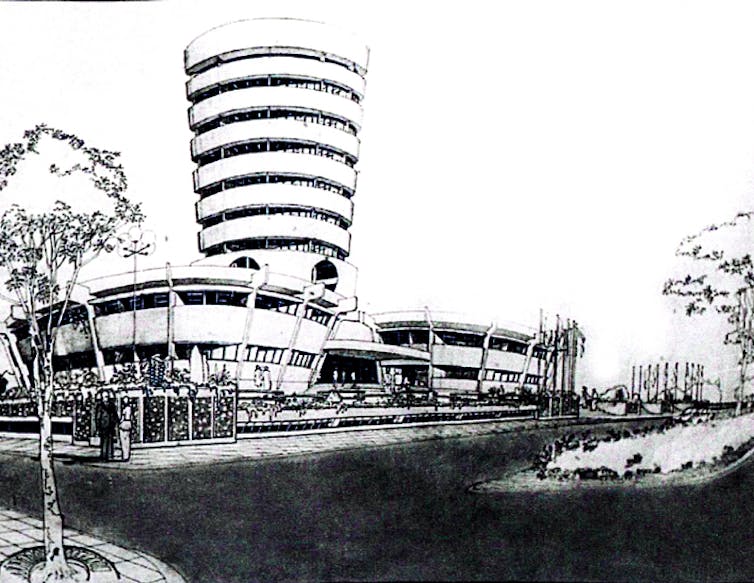

The Unilever Archives in Port Sunlight, United Kingdom, host a vast collection of items documenting the United Africa Company (UAC). A wholly owned subsidiary of Unilever, the UAC was a vast trading and manufacturing empire that itself in turn owned and managed numerous subsidiaries ranging from retail, textiles, timber, and raw material extraction mainly, but not exclusively in the British West African colonies. The scale of the UAC venture throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth century, the company’s role in colonial exploitation, as well as its economic and political manoeuvring into the post-Independence period, render its archive both a problematic and rich repository to catalogue and analyse. Archives have been the subject of a body of theoretical writing from post-colonial perspectives. This has framed the archive as both a locus of power and a technology of domination in and of itself. As the archive of the largest British business in West Africa, and one deeply implicated in the colonial patterns of resource and capital extraction in the region, the UAC archive can equally be theorised in this way. Yet, the UAC archive is also punctuated by moments of hesitancy, contestation, and challenges to the UAC’s attempted hegemony.

The UAC produced an archive as a by-product of the everyday transactions of business in the African colonies: its reports, board minutes, marketing plans, press releases, and ledgers have subsequently been ordered, catalogued, and cared for by a team of curators and archivists. But the UAC also pursued archival impulses of its own: UAC staff collected maps, African artworks and ephemera, personal correspondence and memoirs, as well as taking, collating and cataloguing thousands of photographs between 1880 and 1980. This impulse to collect and catalogue the African world around it shows the UAC’s attempts to impose an archival logic on the diverse, even unwieldy, business empire that it controlled, or attempted to control.

For architectural historians, the photographic collection is of particular interest with its bias towards recording buildings, places, people, and special events. The vast amount of visual material was produced by employees working for different subsidiary companies, each with their own objectives, vantage points, and outlooks. The contributors and content are also diverse in their geographical reach and emphasis, with records spanning vast tracts of the African continent, as well as smaller forays into the Middle East, India, and the Americas. Overall, and in coherence with the nature of a corporation which was indeed multiple, internally diverse, and geographically spread out, the collection appears as a corpus of interrelated but distinct archives each with their own provenance, consistency, detail, and granularity of data.

Considerable effort and expense were devoted to producing and presenting this photographic material. Each subsidiary produced its own documentary evidence by developing a visual record or compendium of their businesses that sat alongside the accounting records and lists. In providing sound evidence that business activity was taking place, the photographic medium was particularly useful to the parent company. Taken with a specific agenda and focus, the photographs were processed and printed before being selected to feature in specially produced albums and often accompanied by printed captions or handwritten comments. In many cases, the photographs became a surrogate for travel as many of the directors and business managers had never visited Africa and had no first-hand conception of what their business interests and assets looked like.

The images demonstrated that stores had been built, that goods were properly stocked on the shelfs and that everything was ‘as promised’. It provided reassurance for owners and shareholders, but also became a form of advertisement as is reflected by the careful organisation of these documents in the archive’s Public Relations folders. Through the photographs, distance and geographical separation seemed less important as the visual evidence which they offered ultimately delivered a sense of proximity by bringing a particular version of Africa back to the European shareholders. Photographs were meant to create a familiarity which could justify the company’s overseas presence and show that a colonial territory was ripe for development, therefore reassuring investors as well as European staff.

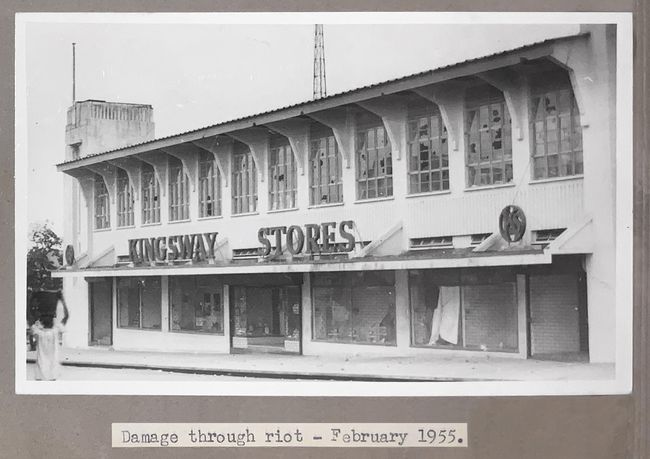

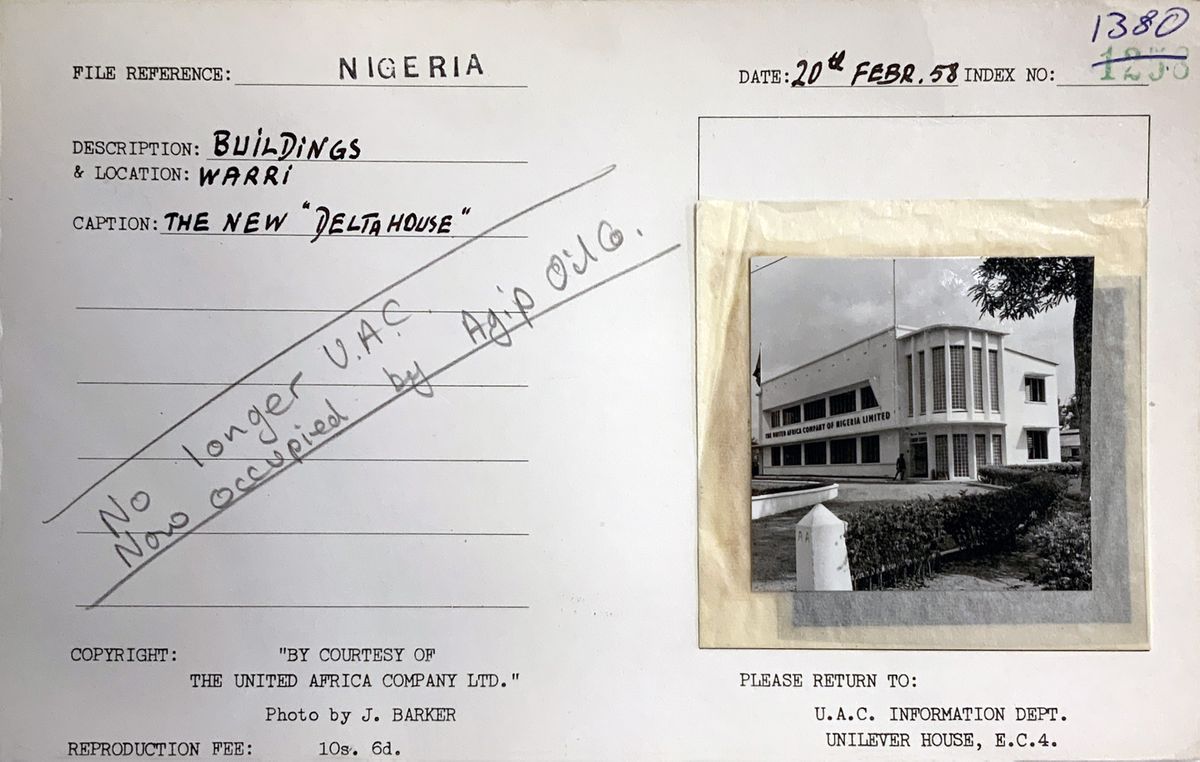

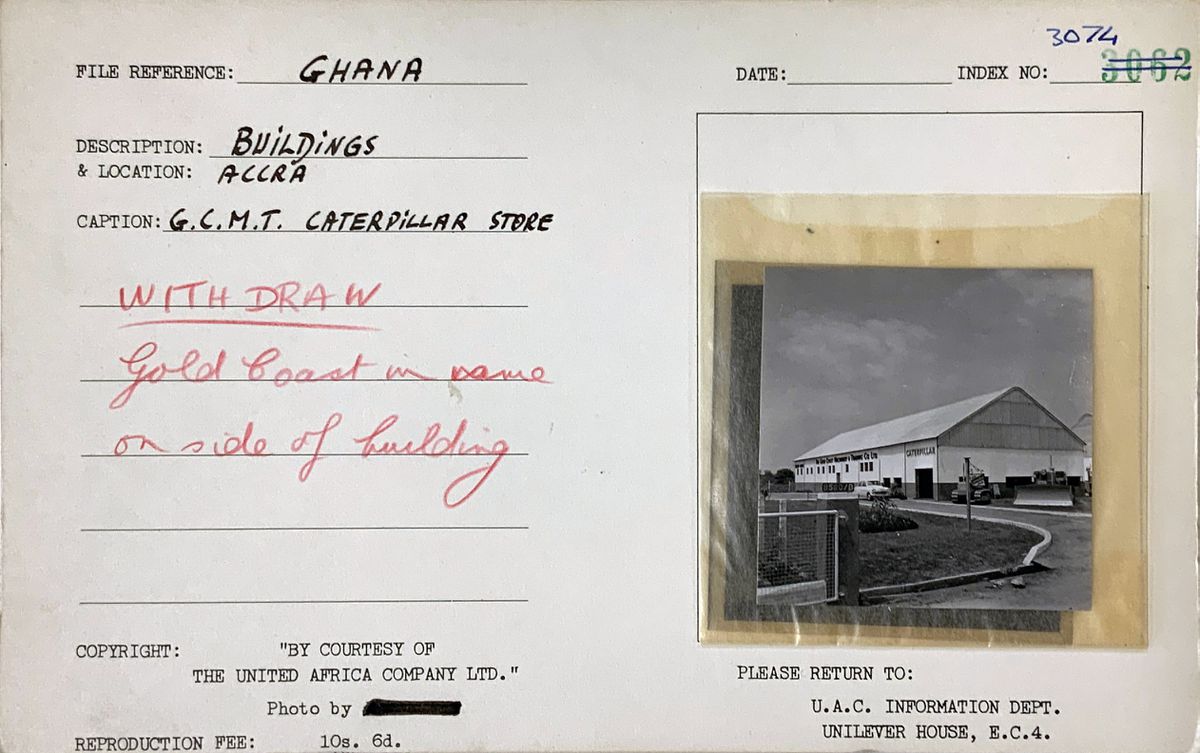

Because of the peculiar role of the photographic documentation for UAC’s activities, the forms of their collecting, defining, and claiming, offers a vantage point from which we can see how the company viewed, perceived, and chose to record the African social and physical environment. The image library was not fixed – it was added over time, revisited and modified. Titles were remade, notes were added, reflecting not only the transformation of the built environment, such as the extension or refurbishment of the company’s premises, or the acquisition or selling of properties, but also the shifting political situation after elections, riots, or strikes and the resulting legitimacy challenges that the company faced.

Such reworking of the archive is especially evident in those sections of the archive in which photographs have been selected and mounted onto cards, as a compiled photography library arranged first by country, then by themes. This collection was compiled to assist the production of marketing reports, company magazines, newsletters, press releases, and advertisements. The production of these publications and public relations material required the finest images and a cataloguing system allowing them to be quickly located. The notes written on the cards indicate that the UAC staff exercised a control towards what was deemed appropriate and suitable for the company’s image.

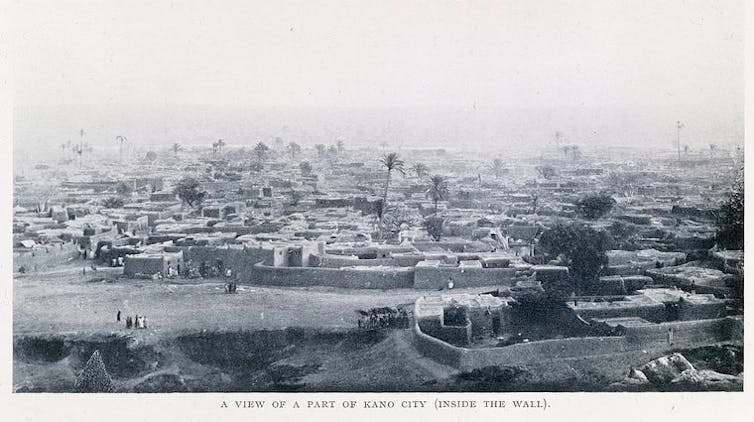

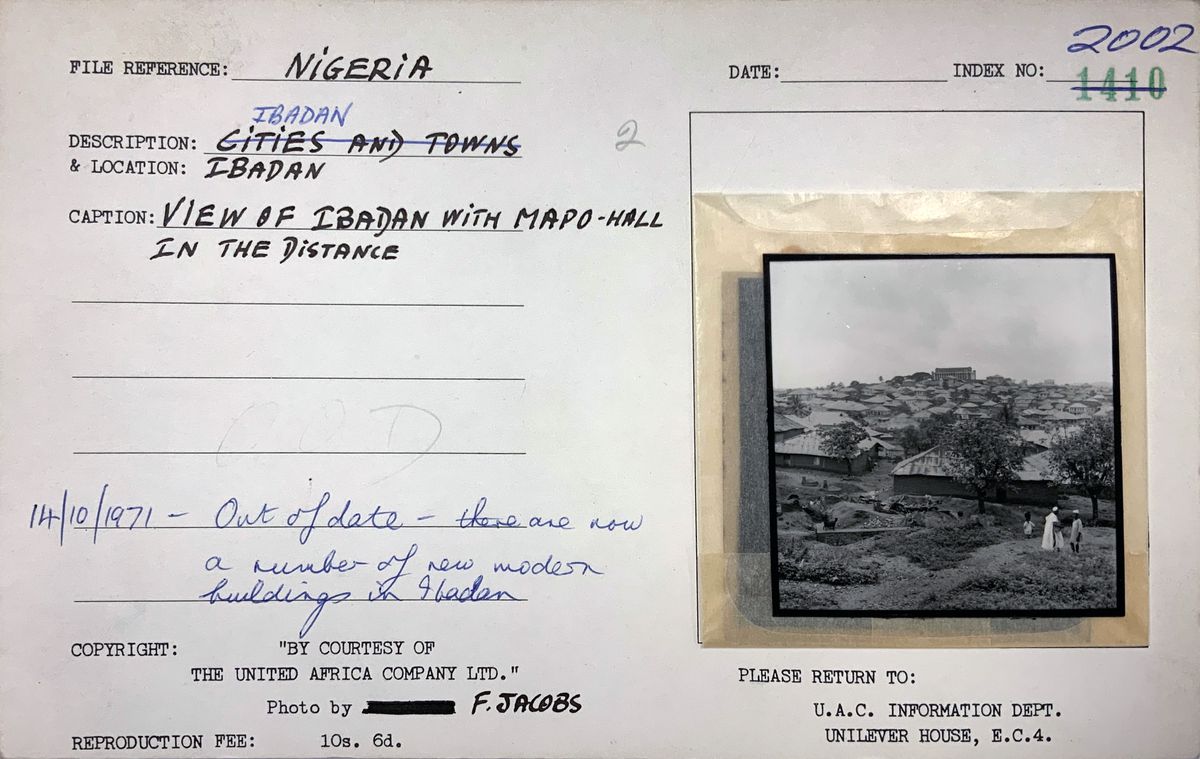

On some of these cards the captions were edited replacing terms which were perceived as outdated or inappropriate. Hence, an image described as “Native workers” was subsequently crossed out and replaced with “African workers”, before being relabelled again as “Employees”. In other instances, “African huts” was replaced by “African homes”, and “European Housing” was renamed “Management Housing” to reflect the Africanisation process of the 1950s – the recruitment and promotion of African staff within the company – which the UAC had embraced as a strategy to repair its legitimacy during the decolonisation phase. Some other images, instead, were marked as ‘to-be-withdrawn’ because the signage of shops of factories employed colonial toponyms which, after independence and for obvious reasons, had become offensive for African audiences. Whereas an image of Ibadan showing a district of low-rise houses built with adobe bricks was deemed no longer usable as it probably conveyed an unwanted sense of precariousness to the public and especially to potential investors.

We don’t know who exactly was making these decisions and how frequently the images were reassessed and relabelled. Unlike the archiving process where archivists generate titles, here they formed part of an image library. However, the fact that the photographs, rather than being re-mounted onto new cards were instead amended by striking through older labels, suggests that perhaps this context was considered valuable, if outdated. Nonetheless, letting this meta-analysis of the archive and its shifting cataloguing and labelling strategy to emerge, required challenging the traditional way in which archives are experienced.

Moving beyond the catalogue

We rarely get to see the archive in the way that one can peruse the books of a library. Instead, we experience it with no direct access to the stores and therefore no opportunity to examine the collection in person. In most cases, files are brought to the researcher after consulting a catalogue, making requests and completing slips and are examined one file at a time. While there are obvious reasons for such restrictions which aim at ensuring the integrity and safety of the material, the necessity of surveillance imposes an examination of the material in extremely compartmentalised or limited ways.

In our research project ‘The Architecture of the United Africa Company: Building Mercantile West Africa’ we have questioned this approach and attempted a different procedure that granted the research team access to the archival storage spaces. ‘Open access’ to the collection has been granted to the research team which has enabled browsing and the ability to quickly sample a box or file without even removing it from its location in the storeroom. The research team has been given extensive training in basic archive procedures, manual handling and health and safety. Retrieval slips were still completed and utilised, but the physical act of obtaining the files and accessing the store rooms was granted to the research team enabling the archive team to focus on their day to day work. The ability to compare boxes, view multiple files, or simply randomly ‘dip’ into boxes has enabled a far greater appreciation of the entire UAC collection, has accelerated our ability to ‘get through the material’, and also reduced the labour for the archives team. Viewing all the photograph albums on the shelves and to see how one album compares in size and scale to the others as well as the ability to visualise the files and their arrangement has helped us to understand the business structure in ways that would not have been possible otherwise.

This procedure, which was made possible by the prolonged collaboration between the academic team and the archive’s management team, has enabled a different working method to emerge. If the re-captioning of UAC’s photographic collection testifies how European capitalism coped with political change and pragmatically adapted itself to the shifting paradigms in the decolonisation phase, acknowledging such additional layers require ‘moving beyond’ the catalogue. The stratification of meanings and orientations which took the form of an almost curatorial approach to the cataloguing of the photographs reveals the biases and the shifting sensitivities of the actors involved in the production and management of the archive. However, such a critical interpretation of descriptive practices requires questioning the traditional interface between archivist and researchers, ultimately allowing engagement with the archive as a complete and stratified entity.

Notes

1 The term “peon” is also found on other material from the Pierre Jeanneret fonds.

2 The word has several meanings across times, languages, and cultures. Not all of them will be covered in this text. It also refers to the pawn in a chess game and to a low unit in some strategy computer games, for example.

3 William Wirt Howe, “The Peonage Cases,” Columbia Law Review 4, No. 4 (April 1904): 279.

4 Pete Daniel, “The Metamorphosis of Slavery, 1865-1900,” The Journal of American History 66, No. 1 (June 1979): 89.

5 Daniel, “The Metamorphosis of Slavery,” 1979.

6 Peonage is not exclusive to the United States. Various forms of “peonage” have existed or still exist across the world.

7 Collins English Dictionary, s.v. “peon,” accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (1981), s.v. “peon.”

8 Collins English Dictionary, s.v. “peon.”

9 “Peon Pay Scale, Pay Grade, Pay Matrix, Salary & Allowance After 7th Pay Commission,” 7th Pay Commission Info, accessed November 15, 2021, https://7thpaycommissioninfo.in/peon-pay-scale-grade-matrix-salary-allowance/#:~:text=Peon%20Pay%20Scale%20under%207th%20Pay%20Commission&text=That%20means%20the%20salary%20of,7000%2F%2D%20per%20month.

10 Government of India, Ministry of Labour & Employment, Directorate General of Employment, National classification of occupations-2015 (Code Structure) I, (New Delhi: National Career Service, 2015), https://www.ncs.gov.in/Documents/National%20Classification%20of%20Occupations%20_Vol%20I-%202015.pdf.

11 Dr. Sangeeta Bagga, Zoom meeting, November 19, 2021.

12 Vikram Bhatt, Zoom meeting, November 25, 2021.

13 Dr. Vikramāditya Prakāsh, Email exchanges, November 2021.

14 At the request of Jane Beverly Drew, one of the three architects with Pierre Jeanneret and Edwin Maxwell Fry responsible for the design of most of the government housing, an additional fourteenth type, known as “cheap houses,” was designed by Drew for, the previously unaccounted for, government employees who were earning the lowest-wage. Kiran Joshi, Documenting Chandigarh: The Indian Architecture of Pierre Jeanneret, Edwin Maxwell Fry, Jane Beverly Drew (Ahmedabad, India: Mapin Publishing Pvt Ltd.; Chandigarh, India: Chandigarh College of Architecture, 1999), Volume 1, 43. Sarbjit Bahga and Surinder Bahga, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret: Footprints on the Sands of Indian Architecture (New Delhi, India: Galgotia Publishing Company, 2000), 131.

15 Bagga also adds that this new housing typology for the “peons” continues to this day, with the same purpose, function, and responsibility of roles.