Livelihoods and culture under threat in Ghana’s historic port of Jamestown

Plans are afoot to replace the historic Ghanaian fishing port of Jamestown with a Chinese-backed mechanised factory.

This is a move that will destroy traditional livelihoods, as well as damage the historic built environment. It will drastically change not only the tangible fabric of this historic town, but also impact the fishing methods, market traders and community that’s reliant on the sea.

Since 2011 I have been researching the history of Ghanaian architecture and urbanism, and have been particularly struck by its impressive collection of heritage structures and associated narratives.

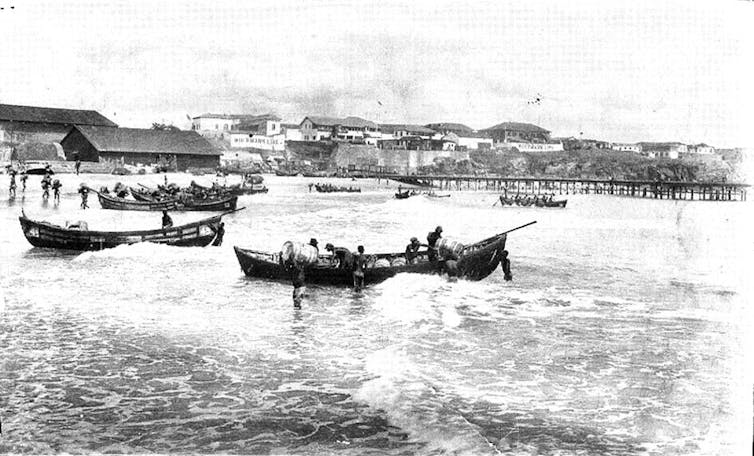

The harbour at Accra’s district of Jamestown was built to provide shelter from the heavy surf that pounds this part of the coast. The breakwater and pier were equipped with railway tracks, gantries and cranes to handle the large produce exports following the cocoa boom of the early 1900s. The wealth created from this trade saw some fine buildings being built. An array of warehouses, stores and villas survive (some very precariously) in Jamestown to this day.

Courtesy of Wirral Archives

The shallow waters of the harbour utilised smaller surf boats who ferried the goods in and out to the ships anchored in deeper water. The creation of new ports rendered the Jamestown harbour superfluous by the 1950s and it was no longer used for international trade.

While this profoundly affected the livelihoods of the surf boat owners, as well as the economic prosperity of the Jamestown area, it has still remained an active harbour, returning its focus to fishing. New canoes are still built on the beach, nets are made, repaired and dried, and a large, if casual, fishing market trades off the shore.

Although described as a beach, it’s still a working harbour rather than a place for leisure. Businesses, residences, schools, places of worship and bars have all been established on the beach and a large population considers it their home and community. The place has a very different feel to the rest of the city. It has an intimate connection to the sea, dictated by the tides, rituals, songs and danger that accompanies all fishing communities.

It is “informal”, sometimes appears anarchic, and while not suitable in its current format for freight shipping, its potential for commercial development has caught the attention of the municipality and international investors.

New development

Earlier this year a billboard was suddenly erected on the beach displaying an “artist’s impression” of how the beach is to be developed. It’s a disturbing image in many ways, showing the beach completely cleared of its inhabitants. There’s also a large car park and a series of somewhat bland sheds or factories. There is not one single canoe in sight.

Iain Jackson

The proposal (and its backers) see this site as a convenient place to construct a new factory for the mechanised processing of fish. There is nothing inherently wrong with this as an idea. But the current proposal would not only occupy a prime site with historical significance: it would displace a large community along with their heritage, skills and traditions.

There are four main considerations that have not been addressed by the current proposal. And with the beach already being cleared of its residents and traders, time is running short.

Seafront heritage site: A shoreline development with an historic waterfront requires sensitive and appropriate proposals. A failure to deliver this undersells the site’s potential. It is not appropriate for a factory and car park to be placed on this important plot.

It is hard to imagine any other international port city using its most important natural features in this way. The attractive view over the ocean offers lots of possibility for this site. Reducing it to a fish-gutting production line is shortsighted and lacks ambition.

Community discussion and liaison: The settlements and businesses located on the beach are “informal” (like most of Ghana’s economy). But this must not discount or invalidate their contribution to future development. No one is more invested in this place than the current population, part of the minority Gā community, with their own language and traditions, who have lived and traded here for centuries.

Individual fishing boats and their small hauls may not be the most efficient or lucrative methods of extracting the bounty of the sea. But they bring many advantages. The main traders (and controllers) are women affectionately known as “mammies”, who set the prices and manage supply.

This matriarchal system has been largely responsible for ensuring a strong community. Whilst these traders are fiercely competitive, they care for each other and their lives. Memories and stories are inherently bound to this place – the proposed factory would completely undermine and destroy this market and cohesion.

Mechanised production would also result in fewer employment opportunities. The power would be taken from market traders and fewer fishermen would be required.

Fish stock: Environmentally the mechanised processing and trawlers would be disastrous for the fish stock. The existing method marries periods of fallow with festivals, allowing the sea to recuperate and replenish. There is a rhythm to the current fishing method that responds to the seasons and traditions. It is unlikely this approach will be respected by the new process and the factory’s profit driven approach.

Tourist potential: The first place tourists visit when arriving in Ghana is usually Jamestown and the harbour area. Its two former slaving forts and the historic mercantile core of the town, coupled with the array of festivals and events, have so much potential as revenue creators.

Read more:

Igniting public space at the Chale Wote street art festival in Accra

They must be treated as rare commodities, not as cheap development plots. If this district is gradually eroded, its natural features, historic charm and engaging community dismissed, then what else is there for visitors to see in Accra?

In the last six months eviction processes have started to clear the beach. This is an earnest plea for this proposal to be rethought – and for this fascinating part of the city to be regenerated in a way that celebrates and respects the history and people of Jamestown.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.